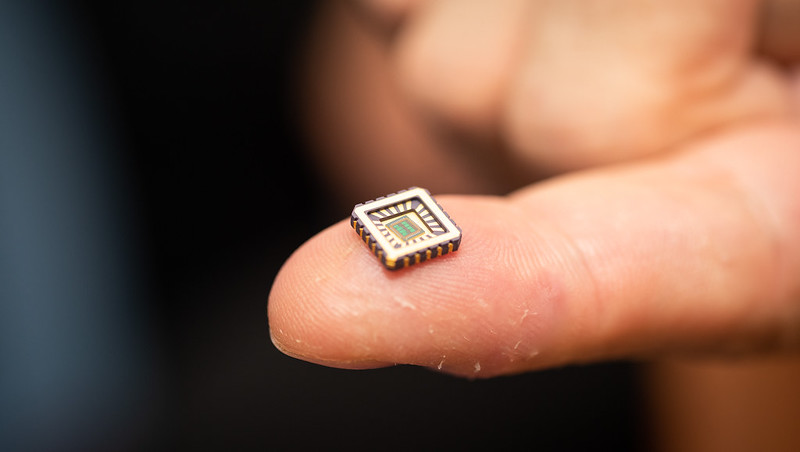

Current chip shortages plaguing manufacturers could be resolved with new hardware agnostic systems for vehicles, domestic chip manufacturing and silicon. By Christopher Dyer

Increased dependency on computing and smart phone technology has contributed to rising semiconductor shortages for major technology and automotive manufacturers. Many have been forced to pause and limit production as chip supplies fail to reach plants.

Western players are now reevaluating their dependency on major producers such as Taiwan’s TSMC, with governments instead opting to develop domestic chip industries. New chip manufacturers and software solution companies have emerged, looking to capitalise on limited supplies and political drives for technical independence.

Sonatus, a US-headquartered technology company, aims to disrupt the microchip industry. Its Chief Executive, Jeff Chou, believes hardware-agnostic systems could innovatively solve the chip shortages.

Coronavirus’ impact

The pandemic has critically damaged current global supply chains, with many microchip manufacturers struggling to fulfil export demands. Sonatus survived in part thanks to Hyundai’s backing and effective management of its own supply chains. Chou explains that some of the best and most prepared manufacturers “are self-aware enough to realise that they have very long design cycles,” and so view the chip shortage as a “short-term phenomenon.” Using long design cycles allows manufacturers to understand, analyse and anticipate how problems will affect the production of future models.

Hyundai and Sonatus have been exceptionally diligent in their approach to mitigating the impact of shortages on Hyundai’s models and sub-brands. Moving further into the high-end segment has also benefitted the company, with models such as the Ioniq 5 and luxury sub-brand Genesis models depending more deeply on software to ensure model functionality. The shortage’s impact is perhaps more pronounced on the compact and sedan car segment, the construction and delivery of which still heavily rely on microchips. Hampered further by price limitations, an industry-wide shift towards software-based approaches in these segments remains a distant prospect.

“I think OEMs are beginning to realise the need to decouple software and hardware, and prevent shortages in the future,” Chou explained. He believes Sonatus is in a unique position to lead the way in software-orientated hardware solutions. Integrating software into formerly hardware heavy designs means that automotive development can be continuous, and improvements can be implemented without the need to release new model iterations.

For example, Tesla uses a homogenous architecture and over-the-air updates to ensure its vehicles remain updated with the latest technology. Providing software that integrates well with dynamic hardware could allow for a plug-and-play system for manufacturers seeking to use existing architectures with limited chip supplies.

The horizon of hardware-agnostic systems

The pandemic and microchip shortages forced manufacturers to innovate with limited resources. Sonatus believes automotive development will continue without dependency on chips, instead using hardware-agnostic software to implement new features, resolving the need for traditional microchips. To realise this however, Chou argues that the industry will need to rebuild automotive manufacturing architecture around “more generic software and hardware systems.”

“Generic architectures can bring new features to market quicker,” he says, adding that this could reduce costs for both manufacturers and consumers. With the price of chips increasing as supply outstrips demand, ensuring this cost isn’t forced onto the consumer remains an important consideration. “Economically it makes sense because you have more leverage,” he said. “Economies of scale make generic architectures easy to implement.” With many high-demand electric vehicles (EVs) still divisively expensive and continuing to use conventional microchips, hardware-agnostic systems could ensure manufacturers can meet demands while keeping costs accessible for consumers.

Social and technical independence

The pandemic also illustrated how the automotive industry is dependent on imported components. Growing tensions in the East Asian peninsula have recently brought this into focus. Taiwan supplies a significant portion of the world’s microchips, something China remains conscious of as it reviews its expansive foreign policy approach. With China’s current chip industry lagging the west, Taiwan looks increasingly vulnerable as the US also imposes further sanctions on one of China’s biggest electronic manufacturers, Huawei.

Chou acknowledges this, suggesting that TSMC’s presence in the area rationalises why Taiwan is under extreme pressure. “If TSMC wasn’t there, the [socio-political] impact of whatever China does would be less from a business standpoint.” With shortages exacerbated by political tension, domestic chip manufacturing is being seen as a more viable alternative to meet growing microchip demands.

An increase in new manufacturers will create more diverse opportunities for microchip development while also providing another important source of revenue for countries financially struggling after the pandemic. Ensuring manufacturers have enough financial and political backing would also facilitate a rapid expansion.

The US government is keen to encourage this, with the Senate passing a bill in June 2020 providing incentives for new chip manufacturers, including tax breaks and government funding for research. “I am very, very happy that the government is doing something about it and trying to bring that back locally,” Chou said. “It’s going to be great for the country in terms of stabilising our dependency on foreign companies and I think it’s going to spur innovation.”

The chip shortage has shown the value of investing in domestic automotive manufacturing. There is now a clear shift and impetus to reindustrialise for the digital age. The European Union, for instance, has reiterated its commitment to Reindustrialisation 4.0, a programme based on the continued implementation of Industry 4.0, and designed to bring industry back to the centre of Europe. This would be achieved by implementing more financial and political support for businesses looking to move into the computing and microchip industry. The UK has a similar plan under Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s levelling up scheme, providing new manufacturers similar backing to the US policy. Japan has also reiterated its own drive to bring outsourced industry back to its shores, such as automotive manufacturing and chip production.

Future of the chip industry

As technological dependency grows, microchips will remain an essential component in future products both within and outside the automotive industry for the foreseeable future.

Prices are also likely to remain the same until new chip types are brought into wide-scale production. Chou was keen to reinforce this when discussing the possibility of silicon carbide microchips. He says these will be “the next oil” for the microchip industry and could provide “more efficient and cheaper approaches to developing systems.” The resources may be easier to source while also providing an important stopgap between software and hardware convergence.

Silicon microchips are being developed by all microchip manufacturers in the automotive industry, but Chou admits that their time-to-market “is longer than software and more costly.” He maintains that it will be part of the next stage of automotive innovation. Understanding the next step of the shortage could prove difficult, as he notes: “The shortage will vary in severity from industry to industry and in the automotive sector from manufacturer to manufacturer.” Whatever the future holds for both hardware-agnostic systems and silicon microchips, it will take time and funds to ensure they become both cost-effective to develop and accessible to implement.